Why is increased recycling not leading to reduced production of virgin raw materials?

You would be forgiven for imagining recycling allows us to put a stop to the endless production of waste which has become ever more recognised as an ecological disaster in recent times. Actually, our current method of recycling has not led to a world where the same waste we put in our recycling bins circulates efficiently, from waste to product, over and over again. In fact the production worldwide of plastics is expected to grow to 20% by 2050, the most polluting material is increasing in production (Vidal, J.) . Waste we carefully separate in wealthy countries can end up dumped in less wealthy, far away ones, causing pollution, damaging worker’s health and ultimately not being recycled at all (Vidal, J.). Even that which doesn’t get exported can end up incinerated(Wecker, K.).

As a product designer, I want to design products which take their environmental impact throughout their entire life cycle into account. One of the ways of doing this is by choosing materials which are easily separated from one another, so no glues or (fused) multi layer materials. This is done to allow the materials to be recycled at the end of life, something many of us are familiar with from separating our waste at home. I think that to design with the end of life of a product in mind in an informed way, I need to know the pitfalls of our current recycling system. After initial research I saw it is actually a more complex and dirty process than it can often first appear.

With this essay I want to present the problems which stood out to me as I tried to comprehend the current industrialised system of recycling. I will also take a look at local and communal systems which offer alternative perspectives on recycling which solve or sidestep these problems.

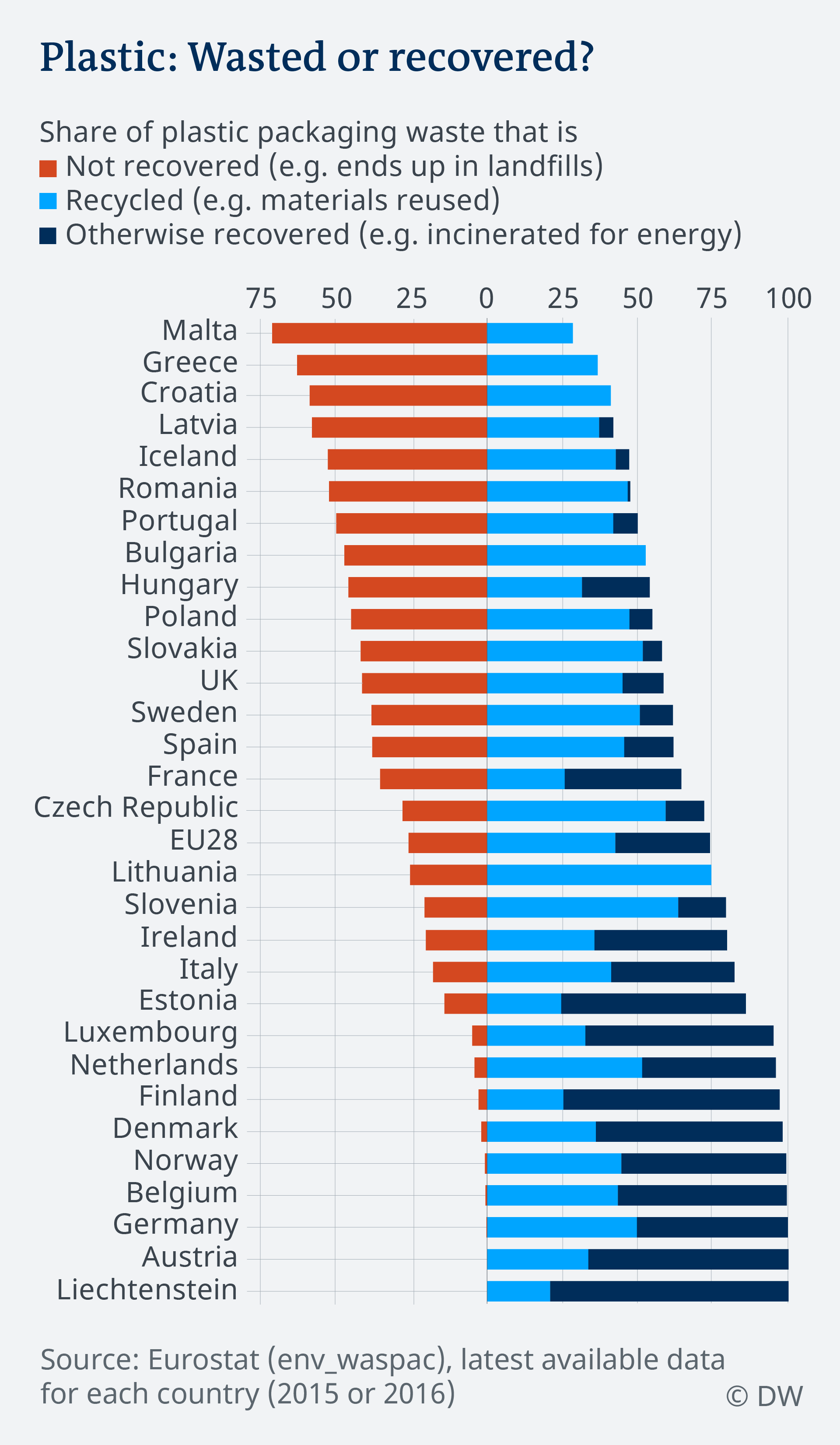

Recycling isn’t working as we so often think it is. The above graph shows that much of what we put in our recycling bins doesn’t end up being recycled.

The social consequences of the production of waste and its management are not prioritised in a profit driven system

rom my research, I repeatedly came across what I think is a core reason why our current system of recycling won’t lead to a reduction in production; the social consequences of the production of waste and its management are not prioritised in a purely profit driven system.

New Plastic is cheap, cheaper than recycled (Hicks, R). In a world dominated by free trade, if the environmental impact of what you produce is not linked to a monetary incentive then it doesn’t factor into decision making and plastics will continue to be a favourable choice for producers. Unregulated, globalised capitalism leads to materials for products being chosen due to profitability reasons, with little to no consideration for its end of life. This is especially true for low profit margin, “fast moving consumer goods”, often found in supermarkets, which are responsible for most plastic waste (Schlosberg, D). It is simply cheaper to use virgin raw materials instead of recycled ones. Thus production of these materials is growing e.g. plastics. With an increasing focus on sustainable energy sources, the biggest growth sector for oil and gas companies is plastics. The increased extracting of natural gas in the last decade has brought prices of raw materials for plastics down (Young, R., Kramer, F., Schwartz, E., Sullivan, L.).

Similarly to the selection of materials by manufactures, the recycling companies have no incentive to reduce the amount of waste which is produced. In a profit driven system, it is actually in these companies best interest for the amount of waste to increase.

The capacity of recycling facilities in the West have not grown in proportion to the amount of waste produced because exporting is cheaper. In the UK for example, a company can export waste abroad and still receive the full subsidy from the government for recycling (Martin, N). It is not investigated how much of this waste actually ends up recycled in the destination country . This incentivises exporting of waste for the recycling companies in high wage countries to lower wage ones. About 2/3 of all UK plastics are exported (Franklin-Wallis, O.)

Plastic waste is finding its way to other countries in the region since China banned many types of plastic imports in 2018. Indonesia is one of the countries which has seen a marked increase in plastic waste being dumped and burned (above)

Plastic waste is finding its way to other countries in the region since China banned many types of plastic imports in 2018. Indonesia is one of the countries which has seen a marked increase in plastic waste being dumped and burned (above)

Recycling was initiated by plastic manufacturers

recycling”, the recyclers making the decision to do so must be aware that these waste bails are almost impossible to recycle into useful new material. They must surely also know that the plastic is not likely to be processed in a way which is environmentally responsible or which is safe for the workers because if we cannot recycle all of this waste in rich, highly educated countries (Schlosberg, D), how do we expect these other countries with fewer resources to do it?

Plastic gets sorted, shredded and then washed before re-melting. Waste water from washing is often released untreated into the ecosystem. When the plastic is melted, depending on the type, it can release volatile organic compounds which are toxic. When the profitable waste has been extracted from these imported bales, the remainder can end up dumped illegally or burned in the open. Even if it is processed legally it can end up improperly disposed of because there is simply no proper facility for it to go to (Wang, J) . As long as waste is treated as a simple good to be profited from like any other on the global market, it will continue to be exported/imported. In this way the current recycling system continues to operate at odds with environmental sustainability and the wellbeing of workers.

We actually need to be incentivising recycling locally. That way we can keep the chain short which reduces the number of opportunities for environmental or humanitarian abuses to occur. At the same time keeping recycling close to home enables us to keep an eye on the quality of waste management in an area with common regulations.

How did this current, flawed system come to be? Surely it could have been predicted that it would go this way?

Recycling in the US was first set up as a pilot project by plastics companies in response to threats from city governments to ban certain types of plastics. The intention wasn’t for recycling to really work as we ideally envisioned it in the 70s and still do, it was for recycling to be in place or at least seen to be “in development” so that the sale of plastics could continue without consumer guilt. The plastics bans were avoided (Young, R., Kramer, F., Schwartz, E., Sullivan, L.).

Worries over the environmental sustainability of using so much plastics could now be calmed through the mention of recycling. The general public did not and I think still don’t understand the fact that recycling did not and has not lead to the recycling of all or even most plastics produced. It is estimated 10% of plastics ever produced have been recycled (Vidal, J.).

Reports from the 70s into the viability of recycling by the as a way to greatly reduce waste already predicted the huge complexities of separating the many different waste materials from each other which are still very much open problems today. The report concluded that a system like we now have would run into exactly the problems we are now facing (Young, R., Kramer, F., Schwartz, E., Sullivan, L.).

Shifting the responsibility to hide the problem

Currently, it is the consumer who is burdened with much of the responsibility of recycling. First we must be educated enough to know how to make choices which enable us to lead a life with minimal waste. If you succeed at this you must then have knowledge of how to properly prepare, separate and finally dispose of your waste in order to maximise chances of it being recycled. Much of this education isn’t common knowledge or taught in school nor is it intuitive or standardised. I think it’s obvious that the companies who produce materials and many of the products which eventually become waste have much more of an opportunity to make recycling both more convenient and effective. They should carry a level of responsibility which is appropriate to the amount of power they posses within the system

In response to the growing environmental movement and resistance to a throwaway culture in the US in the 70s, companies were funders in part of an awareness campaign which focused on the public’s responsibility to take on the problem of waste “people start pollution, people can stop it” (Young, R., Kramer, F., Schwartz, E., Sullivan, L.). This only addresses the visible problem but does nothing to deal with the system or underlying cause.

With an increasing focus on sustainable energy sources, the biggest growth sector for oil and gas companies is plastics. Accordingly, petrochemical companies are engaging more in the cleanup and reduction of plastic via organisations such as Alliance to End Plastic Waste (Young, R., Kramer, F., Schwartz, E., Sullivan, L.), but they will never criticize the material choice itself or the companies who produce it. All the flaws in the which lead to waste needing to be cleaned up in the first place. These cleanup efforts do not come close to matching the estimated growth in the production of plastics from money already invested in scaling up manufacturing facilities. Like with the creation of recycling, they know it is not a feasible solution alone.

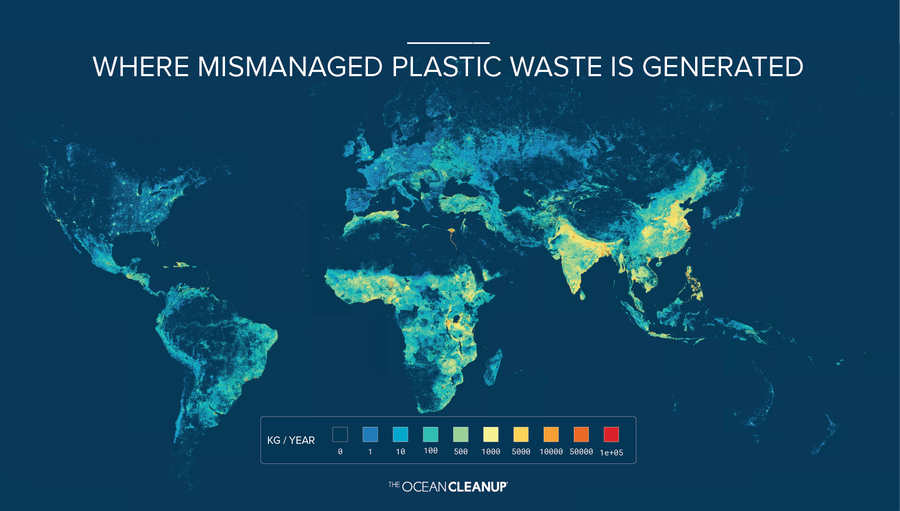

The Ocean Cleanup is an engineering solution to clean up ocean plastic pollution. I think this map from their website shows how they don’t consider deep enough into the system of the problem they are addressing.

The Ocean Cleanup is an engineering solution to clean up ocean plastic pollution. I think this map from their website shows how they don’t consider deep enough into the system of the problem they are addressing.

This is where mismanaged plastic is generated, but how much of the waste was produced by a Western company in the first place? How much is classified

Coca - Cola was one of the original initiators of this focus on cleanup and consumer responsibility (Young, R., Kramer, F., Schwartz, E., Sullivan, L.). They are still finding ways to promote plastics as a guilt free material. They recently were the first client of Print your City, a project by Studio The New Raw which takes waste from a given city and uses it to print street furniture for that city.

I think that Coca-Cola saw this as a way to attach themselves to the popularity around 3D printing at the moment and the idea that we can use plastic indefinitely which this project might imply to those unaware that plastic degrades each time it’s recycled.

I don’t think this is the creator of the project shared that intention however. The project is presented as demonstration of a possible way to use local plastic waste to make useful local objects. The concept involves asking citizens to “pay” for public furniture by separating their waste which will be used for printing. They can customise the design via an app. This is how they would come upon this clean, separated plastic which they use to print the street furniture . The responsibility is still with the consumer but they can see where their waste goes and they know what it will be made into. The choice of street furniture is appropriate I think because it is a long lifespan product made from waste from largely disposable products. This is what we need to be doing, using recycling to turn the existing disposable plastics into more permanent products and then replace the disposables with reusables or circular alternatives.

Local recycling as an alternative

By keeping recycling local we can give it a new framing. Waste produced by locals could be processed into useful new products at a local recycling centre by people who live nearby or even by the owner of the waste themselves. I think this would be a big improvement in transparency and control for the public. Something like this would be close to the opposite of the inscrutable, “black box” system we have now where I place my waste in the right container and trust it will be taken care of in a way responsibly

A project which gives an idea of how a local, one stop recycling/ manufacturing hub could function is the Perpetual Plastic Project by Better Future Factory).

It is an installation where all steps of recycling plastic into new products are in one place: plastic is cleaned, shredded, melted and extruded into filament for a 3D printer before then being printed into a new product. The project is aimed towards education around local possibilities of recycling.

I think this concept could be scaled up to the neighborhood level if there was a solution to locally fund wages of some technicians such as a local waste tax paid when you receive your new product, for example. If it were implemented in this way then the recycling waste of each neighborhood would be in the hands of the people of the neighborhood who have a strong incentive to handle it responsibly; it is valuable to them and importantly, they will have to deal with the immediate negative consequences if they don’t manage their waste in a responsible way. When we have to live with the waste we produce and the problems which come with producing too much of it, we are more likely to take responsibility for the problem. No more “out of sight, out of mind”.

Bibliography

Franklin-Wallis, O. (2019). ‘Plastic recycling is a myth’: What really happens to your rubbish? Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/environ ment/2019/aug/17/plastic-recycling-myth-what-really-happens-your-rubbish Martin, N. (Director). (2018, January 29).

Dirty Business: What really happens to your recycling [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oRQLilXLAIU Sky News report Schlosberg, D. (Director). (2019).

The Story of Plastic [Video file]. Retrieved 2020, from https://www.storyofplastic.org. Wang, J. (Director). (2016).

Plastic China [Video file]. CNEX STUDIO CORPORATION. Retrieved from https://www.cnex.tw/plasticchina Young, R., Kramer, F., Schwartz, E., & Sullivan,, L. (Producers). (2020, March 31).

PBS FRONTLINE: PLASTIC WARS, Season 2020: Episode 14 [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/film/plastic-wars/ Wecker, K. (2018, October 12).

Plastic waste and the recycling myth. Retrieved from https://www.dw.com/en/plastic-waste-and-the-recycling-myth/a-45746469 Vidal, J. (2020, January 02).

The plastic polluters won 2019 – and we’re running out of time to stop them. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/jan/02/year-plastic-pollution-clean-beaches-seas Hicks, R. (2020, May 28).

Cheap virgin plastic is being sold as recycled plastic—it’s time for better recycling certification. Retrieved from https://www.eco-business.com/news/cheap-virgin-plastic-is-being-sold-as-recycled-plastic-its-time-for-better-recycling-certification/#:~:text=The%20price%20of%20virgin%20polyethylene,now%20US%241%2C000%20a%20tonne.

Images

https://www.printyour.city/amsterdam

http://www.perpetualplasticproject.com/evenementen https://www.facebook.com/TheOceanCleanup/photos/a.478028225563564/3476992319000458

https://twitter.com/theoceancleanup/status/1092105443491659776

https://www.dw.com/en/plastic-waste-and-the-recycling-myth/a-45746469